MALVINA HOFFMAN

A Tribute

Born - June 15 , 1887  Died - July 10, 1966

Died - July 10, 1966

Born in New York,

Malvina was the daughter of Richard Hoffman, a music teacher

who began life as a child prodigy of the piano, later the solo

pianist for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Born in New York,

Malvina was the daughter of Richard Hoffman, a music teacher

who began life as a child prodigy of the piano, later the solo

pianist for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

At an early age she was attracted to the

arts, possibly because of the many great opera stars that visited

their home,

At an early age she was attracted to the

arts, possibly because of the many great opera stars that visited

their home,

In 1908 she first met Samuel Grimson. The

violinist had come to play chamber music recitals with her father,

sixteen years later in June of 1924 they were married. Her fathers

failing health inspired Malvina to attempt to make an adequate

portrait of her father and began oil painting. Oils did not seem

adequate, she felt that it required a three dimensional form

and began to sculpt his head. She studied drawing and painting

while still at the Brearley School and for several years worked

under the direction of John W. Alexander.

In 1908 she first met Samuel Grimson. The

violinist had come to play chamber music recitals with her father,

sixteen years later in June of 1924 they were married. Her fathers

failing health inspired Malvina to attempt to make an adequate

portrait of her father and began oil painting. Oils did not seem

adequate, she felt that it required a three dimensional form

and began to sculpt his head. She studied drawing and painting

while still at the Brearley School and for several years worked

under the direction of John W. Alexander.

She completed a marble bust of her father,

which she sent to the National Academy where it was exhibited.

She completed a marble bust of her father,

which she sent to the National Academy where it was exhibited.

After

her father's death, she traveled to Europe with a letter of introduction

from Gutzon

Borglum to Auguste

Rodin. It took her five attempts at presenting the letter

before Rodin would see her. It included photographs of two busts

that she had done, one of her father and the other of the man

she was to marry. Rodin recognized her talent immediately. Her

acceptance as a pupil by Rodin began a friendship that would

last until the end of his days.

After

her father's death, she traveled to Europe with a letter of introduction

from Gutzon

Borglum to Auguste

Rodin. It took her five attempts at presenting the letter

before Rodin would see her. It included photographs of two busts

that she had done, one of her father and the other of the man

she was to marry. Rodin recognized her talent immediately. Her

acceptance as a pupil by Rodin began a friendship that would

last until the end of his days.

By 1915, Hoffman had achieved some fame of

her own. She went on to become a master founder in order to cast

her own bronzes, including the heavy lifting, generally left

to foundry workers. She later published a technical book that

included information on bronze casting, "Sculpture: Inside

and Out".

By 1915, Hoffman had achieved some fame of

her own. She went on to become a master founder in order to cast

her own bronzes, including the heavy lifting, generally left

to foundry workers. She later published a technical book that

included information on bronze casting, "Sculpture: Inside

and Out".

She approached her task with a commitment

to capturing the individual spirit of each subject.

She approached her task with a commitment

to capturing the individual spirit of each subject.

The Paris experience brought her into a

circle of sculptors and artists like Constantin

Brancussi and Ivan

Mestrovic, Paderewski,

Anna Pavlowa,

Gertrude

Stein and Claude

Monet. Mestrovic gave her the advice that she must learn

the principles and the technical side of sculpture better then

most men, because of the preconceived idea that a woman could

not get serious about her art. Rather then deter, this inspired

her to learn all facets of her field of art.

The Paris experience brought her into a

circle of sculptors and artists like Constantin

Brancussi and Ivan

Mestrovic, Paderewski,

Anna Pavlowa,

Gertrude

Stein and Claude

Monet. Mestrovic gave her the advice that she must learn

the principles and the technical side of sculpture better then

most men, because of the preconceived idea that a woman could

not get serious about her art. Rather then deter, this inspired

her to learn all facets of her field of art.

In 1919 Malvina traveled to the Balkans

on behalf of the American Relief Administration to gather information

on the hospital and children's centers.

In 1919 Malvina traveled to the Balkans

on behalf of the American Relief Administration to gather information

on the hospital and children's centers.

In 1930, Stanley Field, the nephew of Marshall

Field I, commissioned Malvina to sculpt and cast bronze figures

depicting the peoples of the world, this was to be her greatest

project and achievement, the creation of " The Hall of Man"

for the Field museum of Chicago. "The Races of Mankind"

is the largest singly commissioned body of her work and consists

of 104 busts, heads and life-sized figures. In preparation for

the exhibit, Hoffman and her husband, S. B. Grimson, traveled

throughout the world to find authentic models for the sculptures.

It took five years to complete. The one hundred bronzes which

make up the "Races of Man" is an incomparable collection

of the various racial types of man inhabiting this world. The

work was very controversial amongst the anthropological circle

of the time. Her work was criticized by social scientists as

too reliant on physical over cultural characteristics. Her bronzes

of the Sengalese Tom-tom Player

and the Shilluk Warrior are examples

of the character she was able to portray in these sculptures.

The prevailing abstract artists of the day saw her work as either

too realistic or too romantic. By the time of her death in 1966,

figures such as her Nordic Type or Bushman Man were dismissed

as anthropologically incorrect, and her work was moth balled.

In 1930, Stanley Field, the nephew of Marshall

Field I, commissioned Malvina to sculpt and cast bronze figures

depicting the peoples of the world, this was to be her greatest

project and achievement, the creation of " The Hall of Man"

for the Field museum of Chicago. "The Races of Mankind"

is the largest singly commissioned body of her work and consists

of 104 busts, heads and life-sized figures. In preparation for

the exhibit, Hoffman and her husband, S. B. Grimson, traveled

throughout the world to find authentic models for the sculptures.

It took five years to complete. The one hundred bronzes which

make up the "Races of Man" is an incomparable collection

of the various racial types of man inhabiting this world. The

work was very controversial amongst the anthropological circle

of the time. Her work was criticized by social scientists as

too reliant on physical over cultural characteristics. Her bronzes

of the Sengalese Tom-tom Player

and the Shilluk Warrior are examples

of the character she was able to portray in these sculptures.

The prevailing abstract artists of the day saw her work as either

too realistic or too romantic. By the time of her death in 1966,

figures such as her Nordic Type or Bushman Man were dismissed

as anthropologically incorrect, and her work was moth balled.

Gradually, in the years since, critics and

the museum itself have taken a different view, seeing in Hoffman's

work not a simplification of ethnic types but extraordinary recreations

of vibrant individuals from different cultures. The figures reveal

more than mere technical prowess and anatomical detail; they

express a feeling of movement, ready at any moment to spring

forth. Malvina's subjects, frozen in a moment of time, in joyous

motion or deepest concentration, exude life.

Gradually, in the years since, critics and

the museum itself have taken a different view, seeing in Hoffman's

work not a simplification of ethnic types but extraordinary recreations

of vibrant individuals from different cultures. The figures reveal

more than mere technical prowess and anatomical detail; they

express a feeling of movement, ready at any moment to spring

forth. Malvina's subjects, frozen in a moment of time, in joyous

motion or deepest concentration, exude life.

The resulting photographs from the trip

appear in her two autobiographies, as well as in several publications

about Malvina Hoffman Malvina was a member of The Association

of Women Painters and Sculptors, which changed its name in 1917,

to The National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors,

and in 1941, to their present NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOMEN ARTISTS,

INC.

The resulting photographs from the trip

appear in her two autobiographies, as well as in several publications

about Malvina Hoffman Malvina was a member of The Association

of Women Painters and Sculptors, which changed its name in 1917,

to The National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors,

and in 1941, to their present NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOMEN ARTISTS,

INC.

Malvina

Hoffman died at her studio-home in New York, New York, on July

10, 1966.

Malvina

Hoffman died at her studio-home in New York, New York, on July

10, 1966.

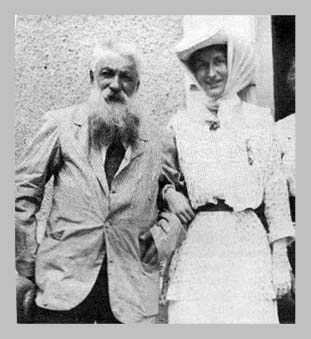

Malvina with her close friend Anna Pavlowa.

|

Sculpture Inside and Out Heads and Tales Yesterday Is Tomorrow Two Sculptures from the "Hall of Man" |